Sep, 27 2025

Sep, 27 2025

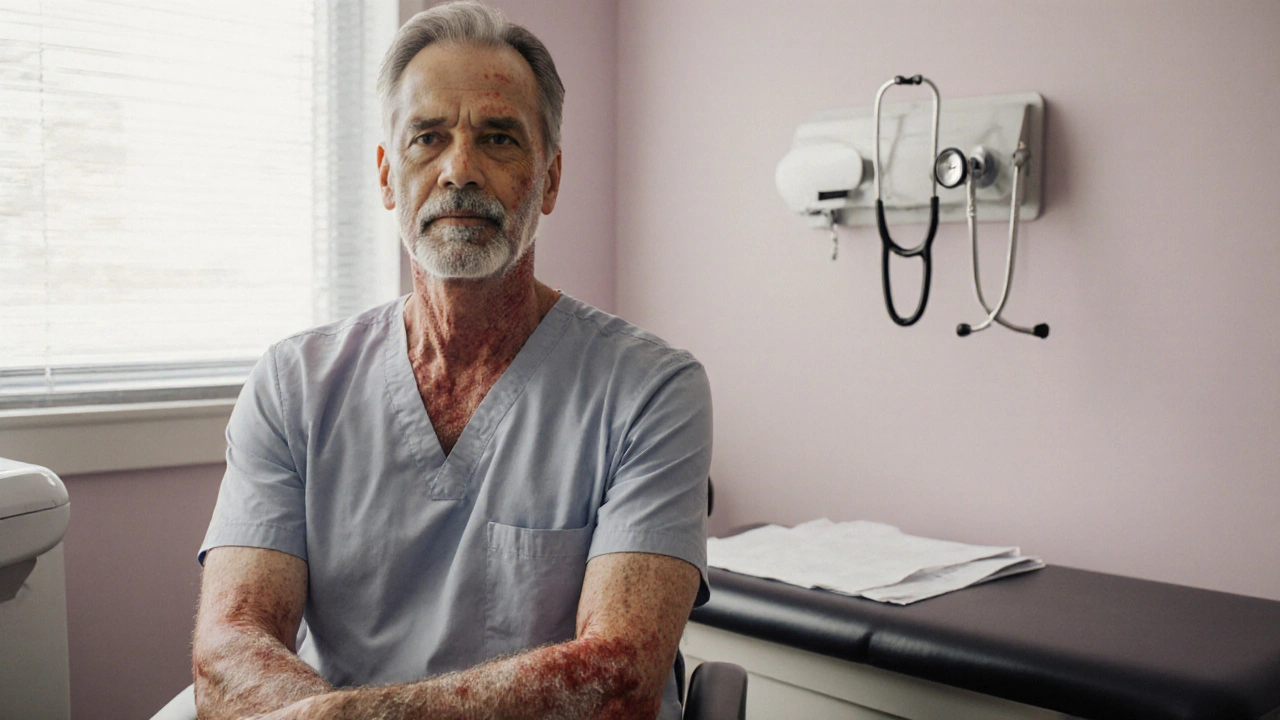

Plaque Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that produces red, scaly plaques, most often on elbows, knees, and scalp. It is driven by an over‑active immune system and affects roughly 2‑3% of the UK population. While skin symptoms dominate the conversation, researchers increasingly recognise that plaque psoriasis often co‑exists with internal conditions, especially thyroid disorders. Understanding why these seemingly separate ailments overlap can help patients and clinicians catch problems early and tailor treatment.

Quick Take

- Both plaque psoriasis and many thyroid disorders are autoimmune diseases.

- Shared cytokines - especially IL‑17 and TNF‑α - drive inflammation in skin and thyroid.

- People with psoriasis are 1.5‑2× more likely to develop Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

- Screening thyroid function at diagnosis and during biologic therapy improves outcomes.

- Biologics that block IL‑17 or TNF‑α can stabilize thyroid autoimmunity, but monitoring is essential.

What Is Plaque Psoriasis?

Plaque psoriasis belongs to the broader family of autoimmune diseases. In these conditions, the body’s own immune cells mistakenly attack healthy tissue. In psoriasis, T‑cells release pro‑inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin‑17 (IL‑17) and tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF‑α). These molecules trigger rapid skin cell turnover, producing the characteristic thick plaques.

Genetic susceptibility plays a big role; the HLA‑Cw6 allele is the most strongly linked gene. Yet not everyone with the gene develops the disease - environmental triggers like stress, infection, or smoking often tip the balance.

Thyroid Disorders: An Overview

The thyroid gland regulates metabolism via hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Disorders fall into two main categories: hypothyroidism (under‑active) and hyperthyroidism (over‑active). The two most common autoimmune forms are Hashimoto thyroiditis and Graves disease. Both involve autoantibodies that mistakenly target thyroid proteins, but their clinical pictures differ.

In Hashimoto, antibodies (anti‑TPO and anti‑TG) destroy thyroid cells, leading to low T4/T3 and elevated thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH). In Graves, stimulating antibodies (TRAb) push the gland to over‑produce hormones, causing low TSH and high T4/T3. Both conditions are estimated to affect about 5% of the UK population, with a clear female predominance.

Shared Autoimmune Mechanisms

Why do skin and thyroid inflammation often appear together? The answer lies in overlapping immune pathways. The cytokines IL‑17 and TNF‑α, central to plaque psoriasis, are also active in thyroid autoimmunity. Studies show elevated IL‑17 levels in patients with Hashimoto, suggesting a common inflammatory driver.

Another link is the presence of shared genetic risk loci. The PTPN22 gene, which regulates T‑cell activity, is associated with both psoriasis and autoimmune thyroid disease. This gene‑environment‑immune triad explains the higher co‑occurrence rate.

Finally, systemic inflammation increases oxidative stress, which can damage thyroid follicular cells, further fueling autoimmunity. In short, the immune system’s mis‑fire in one organ can spill over to another.

Epidemiological Evidence

Large‑scale cohort studies from the UK, Scandinavia, and the US consistently report a 1.5‑ to 2‑fold increase in thyroid disorder prevalence among people with plaque psoriasis. For instance, a 2023 British Dermatology Journal analysis of 12,000 psoriasis patients found that 12% had a documented thyroid disorder, compared with 5% in matched controls.

Age and gender matter. Women with psoriasis over the age of 40 are especially prone to Hashimoto, while younger men show a slightly higher rate of Graves disease. The risk also rises with disease severity - patients with a Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) above 10 have a 30% higher odds of thyroid autoimmunity.

Clinical Implications: Screening and Diagnosis

Given the strong link, clinicians should adopt a low threshold for thyroid screening in psoriasis patients. Baseline tests include:

- Serum TSH (sensitive marker for both hypo‑ and hyper‑thyroidism).

- Free T4 and Free T3 (to confirm hormonal status).

- Anti‑TPO and anti‑TG antibodies (detect Hashimoto).

- TRAb (thyroid‑stimulating receptor antibodies) when hyperthyroidism is suspected.

Repeating the panel annually, or whenever psoriasis therapy changes, helps catch subclinical disease before symptoms develop.

| Feature | Hashimoto Thyroiditis | Graves Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune nature | Yes (destructive) | Yes (stimulating) |

| Primary antibodies | Anti‑TPO, Anti‑TG | TRAb (TSH‑receptor) |

| TSH level | Elevated | Suppressed |

| Free T4/T3 | Low | High |

| Typical symptoms | Fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance | Weight loss, heat intolerance, tremor |

Therapeutic Overlap: Biologics and Thyroid Health

Modern psoriasis treatment often involves biologic agents that specifically block IL‑17 (e.g., secukinumab, ixekizumab) or TNF‑α (e.g., etanercept, adalimumab). Because these cytokines are also implicated in thyroid autoimmunity, biologics can have a dual effect.

Clinical observations suggest that IL‑17 inhibitors may reduce anti‑TPO titres in some patients, potentially slowing Hashimoto progression. Conversely, TNF‑α blockers have been linked to rare cases of new‑onset Graves disease, possibly by altering immune regulation. The takeaway? Regular thyroid function monitoring is advised after initiating any biologic.

For patients already diagnosed with a thyroid disorder, coordination between dermatologists and endocrinologists is vital. Adjusting levothyroxine dosage may be necessary when systemic inflammation improves, as metabolism normalises.

Practical Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

- At diagnosis: Order baseline TSH, free T4, and thyroid antibody panel.

- When disease is severe (PASI >10): Flag for more frequent (6‑month) thyroid review.

- Before starting biologics: Confirm stable thyroid status; document any existing antibodies.

- During biologic therapy: Repeat TSH and antibodies every 12 months, or sooner if symptoms arise.

- If new thyroid symptoms appear: Conduct full panel immediately; consider endocrinology referral.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Beyond the direct psoriasis‑thyroid link, several adjacent topics are worth exploring:

- Metabolic syndrome - often co‑exists with both conditions, amplifying cardiovascular risk.

- Vitamin D deficiency - influences immune tolerance and may exacerbate both skin and thyroid autoimmunity.

- Stress management - chronic stress drives cytokine release, worsening plaques and thyroid imbalance.

- Future research: Novel dual‑target agents that modulate both IL‑17 and thyroid‑specific pathways.

Readers interested in the broader autoimmune landscape might next dive into "Autoimmune Disease Clusters: Why One Condition Often Sparks Another" or "Biologic Therapies: Balancing Efficacy and Endocrine Safety".

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need to get my thyroid checked if I have mild plaque psoriasis?

A baseline thyroid panel is advisable for any psoriasis diagnosis, even mild cases. Early detection of subclinical thyroid issues can prevent future fatigue or weight changes that would otherwise be blamed on skin disease.

Can psoriasis medication cause thyroid disease?

Biologics that block TNF‑α have rare reports of triggering Graves disease, while IL‑17 inhibitors may actually dampen thyroid autoantibodies. The risk is low, but routine monitoring is recommended.

What symptoms should alert me to a thyroid problem?

For hypothyroidism look for fatigue, cold intolerance, dry skin, and weight gain. For hyperthyroidism watch for heat intolerance, rapid heartbeat, tremor, weight loss, and anxiety. Many of these overlap with psoriasis‑related fatigue, so a blood test is the best way to differentiate.

Is there a dietary plan that helps both skin and thyroid?

A balanced Mediterranean diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, selenium, and vitamin D supports immune regulation. Limiting processed foods and excessive iodine (which can flag thyroid autoimmunity) may benefit both conditions.

Should I see an endocrinologist if my dermatologist orders thyroid tests?

If the results show abnormal hormone levels or positive antibodies, a referral to an endocrinologist is the next step. Even borderline results merit specialist input when you’re about to start biologic therapy.

Brooke Bevins

September 27, 2025 AT 02:53Wow, I totally feel you on the stress of juggling skin flare‑ups and thyroid tests 😊. Getting a baseline TSH and antibody panel right when you’re diagnosed can save a lot of hassle later. Keep an eye on those numbers, especially if you start a biologic – it’s worth the extra blood work.

Vandita Shukla

October 1, 2025 AT 18:00Actually, the link isn’t just about “stress”; multiple genome‑wide studies have pinpointed the PTPN22 locus as a shared risk allele, and the cytokine profile you mentioned is well‑documented. Screening every six months is excessive unless you have abnormal labs, so the article overstates the frequency.

Susan Hayes

October 6, 2025 AT 09:07Let’s be clear: this isn’t some “American” over‑medicalization – the data from the UK and Scandinavia are crystal‑clear that psoriasis patients carry a real, measurable increase in thyroid autoimmunity. The drama around “new‑onset Graves” is blown out of proportion by a few case reports, not a population trend.

Jessica Forsen

October 11, 2025 AT 00:13Oh sure, because nothing says “I care” like telling someone to “just get a blood test” while they’re already dealing with flaking skin. But hey, if a quick lab can keep the thyroid drama at bay, who am I to argue?

Deepak Bhatia

October 15, 2025 AT 15:20It’s a good idea to talk with your doctor about regular thyroid checks, especially if your psoriasis is severe. Simple blood tests are cheap and can catch problems early.

Samantha Gavrin

October 20, 2025 AT 06:27One must consider the possibility that pharmaceutical companies have an incentive to promote extra screening, thereby expanding the market for costly biologics. While the immunological mechanisms are sound, the push for routine thyroid panels could be financially motivated.

NIck Brown

October 24, 2025 AT 21:33Honestly, people who ignore the thyroid link are just being lazy with their health. If you’re already dealing with an autoimmune skin condition, skipping a basic hormone test is just negligence.

Andy McCullough

October 29, 2025 AT 11:40The IL‑17 axis serves as a pivotal node in the Th17‑driven inflammatory cascade, which is implicated in both keratinocyte hyperproliferation and thyroid follicular apoptosis. Evidence from longitudinal cohorts demonstrates that IL‑17 blockade can attenuate anti‑TPO titers, suggesting downstream modulation of autoantibody production. Conversely, TNF‑α inhibition may disrupt peripheral tolerance, occasionally precipitating TRAb emergence. Therefore, therapeutic stratification should incorporate baseline thyroid serology to anticipate these immunomodulatory off‑targets. A multidisciplinary monitoring protocol optimizes both dermatologic and endocrine outcomes.

Zackery Brinkley

November 3, 2025 AT 02:47Keeping your dermatologist and endocrinologist in sync can make a huge difference. They’ll know when to adjust medications based on how your skin and thyroid are responding.

Luke Dillon

November 7, 2025 AT 17:53Totally agree – good communication between specialists is key, and patients should feel empowered to ask about any new symptoms.

Elle Batchelor Peapell

November 12, 2025 AT 09:00Isn’t it curious how the body’s rebellion in one organ can echo in another, like a hidden conversation we’re just beginning to hear? Our immune system seems to have its own secret language.

Jeremy Wessel

November 17, 2025 AT 00:07Screening is wise, especially before biologics.

Laura Barney

November 21, 2025 AT 15:13Picture this: your skin and thyroid are two rebellious artists, both painting with the same fiery brush of cytokines. It’s high time we stop treating them as isolated exhibits and start curating the whole gallery.

Jessica H.

November 26, 2025 AT 06:20The foregoing article, while comprehensive, suffers from an overreliance on anecdotal observations rather than systematic meta‑analysis. Moreover, the recommendations lack specificity regarding the timing and frequency of thyroid monitoring in relation to different biologic agents.

Tom Saa

November 30, 2025 AT 21:27Life, much like the immune system, balances on the edge of order and chaos; when one piece tips, the whole structure shivers. Perhaps our focus on isolated symptoms blinds us to the grander pattern.

John Magnus

December 5, 2025 AT 12:33The mechanistic overlap between plaque psoriasis and autoimmune thyroid disease is anchored in the dysregulation of Th17 cells, which secrete IL‑17A, IL‑17F, and IL‑22, cytokines that drive both epidermal hyperplasia and thyroid follicular inflammation.

The genome‑wide association studies have repeatedly identified shared susceptibility loci such as PTPN22, CTLA4, and HLA‑C*06:02, underscoring a common genetic scaffolding that predisposes individuals to both conditions.

Clinically, this translates into a roughly two‑fold increase in the prevalence of anti‑TPO antibodies among psoriasis cohorts, a figure that persists even after adjusting for age, sex, and disease severity.

The inflammatory milieu created by persistent skin lesions elevates systemic levels of C‑reactive protein and oxidative stress markers, which in turn can exacerbate thyroid antigen presentation.

Biologic agents targeting IL‑17, such as secukinumab, have been shown in prospective pilot studies to reduce anti‑TPO titres by up to 30 %, suggesting a therapeutic spill‑over effect.

Conversely, TNF‑α blockers like adalimumab have sporadic case reports linking them to de‑novo Graves disease, possibly due to perturbations in peripheral tolerance mechanisms.

From a pharmacodynamic perspective, the half‑life of these monoclonal antibodies necessitates periodic reassessment of thyroid function, ideally at six‑month intervals during the induction phase.

Endocrinologists should be prepared to adjust levothyroxine dosing when patients experience rapid improvements in PASI scores, as metabolic demand can shift dramatically.

It is also critical to monitor for subclinical hyperthyroidism, which may manifest as suppressed TSH without overt clinical signs, especially in patients with pre‑existing nodular goitre.

Incorporating a standardized thyroid panel-TSH, free T4, free T3, anti‑TPO, anti‑TG, and TRAb-into the baseline work‑up ensures that any latent dysfunction is captured early.

For patients transitioning between biologics, a wash‑out period of at least four weeks can mitigate the risk of confounding serological fluctuations.

Health‑care systems should consider developing integrated electronic alerts that flag patients with a PASI >10 for automatic thyroid re‑evaluation.

Patient education remains paramount; individuals should be taught to recognize subtle symptoms such as unexplained fatigue, heat intolerance, or hair loss, which may herald thyroid imbalance.

Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach that aligns dermatology, endocrinology, and primary care yields the most robust outcomes, reducing both disease burden and healthcare costs.

In summary, the intersection of plaque psoriasis and thyroid autoimmunity is not merely coincidental but reflects a shared pathogenic orchestra that can be modulated with vigilant screening and targeted biologic therapy.